As a new chapter unfolds in Zanzibar, Tanzania, in the event of the historic memorandum that was signed between the Government of India, IIT-M, and the Government of Tanzania for setting up the first IIT overseas campus, we roll back a few decades to unearth the story behind IIT Madras and its connection with the German Cold War that resulted in the formation of the now-revered institution

Srivatsan S

At the end of the Second World War in 1945, Germany was on the cusp of facing another bout of unrest. Over the next decade-and-a-half, political, social and economic factors resulted in the formation of the Berlin Wall, which divided the country into the German Democratic Republic (GDR, also known as East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FDR, also known as West Germany). During the Cold War (between 1947-1991), it was common for the two rival countries to offer development support to then developing and under-developed countries, in their larger goal to muscle their influences and to benefit from the bilateral relations they shared.

One of the “largest and most successful educational projects” that emerged out of Indo-German relations during the Cold War, was the establishment of the Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT-M) in 1959, which, when seen from the perspective of FDR, was largely driven by the Cold War foreign policy it shared with India.

While the Sarkar Committee in 1946 recommended that India set-up “at least four technical institutions on the lines of the famous Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA, in the eastern, western, northern and southern regions of the country”, the IITs came into existence only post-Independence.

The rationale behind setting up an institution as influential as IIT-M, which has been ranked as ‘The No: 1 Engineering Institute’ in the country for over five [as of 2023, six] consecutive years by the National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF), caught the attention of German Roland Wittje, Associate Professor, History of Science and Technology, Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Madras.

Anecdotal history

In his research paper titled Engineering Education in Cold War Diplomacy: India, Germany and the Establishment of IIT Madras, a part of a series of papers published in Wiley’s journal under the title History of Science and Humanities, Wittje unearths this rather fascinating nugget of history, examining the social-political events and the motivation behind the formation of IIT-M. Wittje stumbled upon IIT-M’s connection with the Cold War when he was doing the preliminary work for setting up the institution’s archive and was working with Kumaran Sathasivam of the Heritage Centre, IIT-M. A historian of science, Wittje says he was not too familiar with political history and wanted to understand the dogma behind science diplomacy between India and Germany.

Just before West Germany made an offer for IIT-M, IIT Bombay was established in 1958 with support from the Soviet Union. “With [Jawaharlal] Nehru spearheading the Non-Alignment Movement during the Cold War, what West Germany wanted was that India shouldn’t acknowledge East Germany as a sovereign nation,” says Wittje, “During the early phase, Germany got what it wanted from India, in terms of the larger picture of development. In fact, IIT-M is its largest project as far as higher education was concerned worldwide, even though Germany did assist countries like Egypt and South America.”

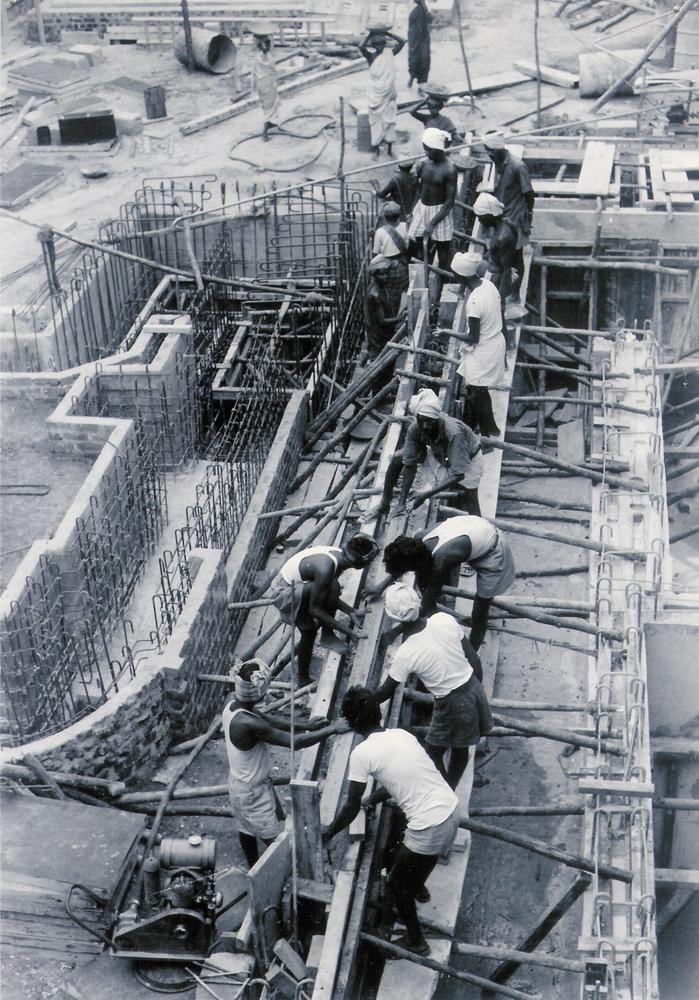

During the course of his research, which involved talking to German experts and their practices at IIT-M, Wittje found out that German faculties were quite specific on the type of character that IIT Madras should embody, as a technical institute. The paper also argues how Mechanical Engineering was and continues to remain the largest faculty at IIT-M.

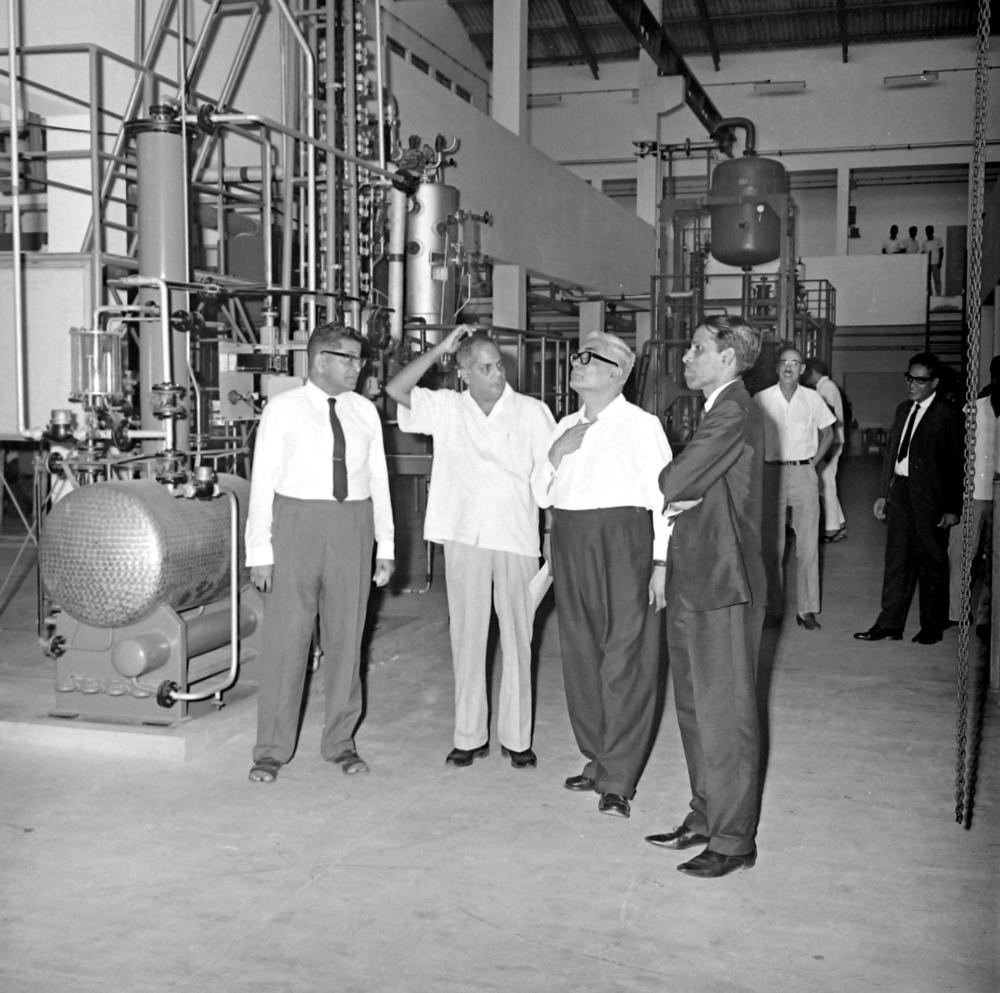

“The German connection continues to thrive at IIT Madras, and it is always interesting to learn various nuggets about how the relationship evolved in the initial years. IIT Madras has benefitted from the attention paid by the Germans in the formative years to foundational technical education and research, as well as to skill development,” said Professor Bhaskar Ramamurthi, [former] Director, IIT Madras.

About the German style of technical education that subscribed to the model focussing on practical exposure than theory, Wittje says, “They [Germany] insisted on practical and a strong workshop-based education. When I spoke to older faculties for the research, they felt that the education students got was actually good. Although the practice-oriented education did not prevail over the years.”

What has changed

Wittje’s paper also brings to the fore the social-cultural relevance of Madras and what the institution meant for its people, though he admits that he is not an expert in South Indian history.

He argues that the location for IIT-M itself had political reasons, “Madras was not the first choice for Germany and they preferred somewhere close to Delhi, also for political reasons,” he says, adding, “They were not opposed to Madras but they definitely didn’t want Kanpur, as they felt it was far more isolated.”

Wittje observes that the collaboration created friction between Indian and German faculties initially, with regard to the mode of teaching. But there was nearly no political influence over the institution soon after the Cold War, he says. “In the beginning, West Germany did not think from a long time perspective. They saw this [IIT-M] as a goodwill gesture. But it was only in the ‘70s did they want to have a techno-scientific international collaboration. And they developed a strategy which was different from other IITs.”

Acknowledging that the paper is still a German perspective, Wittje says he wanted to shift the general narrative: of IIT graduates settling in the US and engaging with software. “That sort of mass exodus didn’t happen with Germany because of the immigration laws that made it a lot easier for Asians to move to the US,” he says, adding that a lot of students continue to reap the benefits of the Indo-German relations.

Which is why even as recently as when Frank-Walter Steinmeier, President of Germany, paid a visit to the IIT-M Research Park in 2018 to further that collaboration. “Part of the reason behind this research was to make the institution understand its own history,” he adds.

This article was first published in The Hindu, Metroplus, and has been reproduced with permission. You can read the article here: https://bit.ly/3R6Mdc9