A decade after its inception, Raftar Formula Racing, the Formula Student Team of IIT Madras, is all set to present its first electric car on a global stage. Ahead of the upcoming Formula Student competition to be held in Hockenheimring, Germany, we look at Raftar’s evolution over the years, and have a chat with its crew members and faculty advisors

Srivatsan S

It’s quarter to three on a painfully sultry Saturday afternoon, where the sun doesn’t show any signs of slowing down. We wipe the sweat from our faces along with the thought that it’s going to be over soon, a sentiment that all of us who have gathered at the Office of Industrial Consultancy and Sponsored Research (IC&SR), IIT Madras, seem to collectively share. Now, it’s just a question of minutes before the demonstration begins.

Amidst all this, we hear chatter emerging from the road that runs parallel to IC&SR where a group of students appear silhouetted against the arms of the banyan trees. They take measured steps mindful of the weight they are carrying along. After all, it’s their baby, born out of a wedlock from ten departments involving cross disciplines.

Amidst all this, we hear chatter emerging from the road that runs parallel to IC&SR where a group of students appear silhouetted against the arms of the banyan trees. They take measured steps mindful of the weight they are carrying along. After all, it’s their baby, born out of a wedlock from ten departments involving cross disciplines.

This is RFR23, the first electric Formula Student car designed and built by Raftar, a team of 40 IIT-M students who share a common passion for automotive engineering and motorsports. Today, we are at IC&SR, where Team Raftar plans to take the car for a quick spin. The moment RFR23 enters the arena, there is palpable excitement among the onlookers who look at the scene with much intrigue. One of the crew members safely jacks the car up from the rear making the RFR23 trudge its way on the road, while the driver, Sai Ashwin, sits in the cockpit like a King waiting to be received by his people.

All of a sudden, the students stop mid-way to discuss something first. Madhav Rajadurai, a third year student of Engineering Design and the current captain of Raftar, goes running to the crew. They all seem concerned. “I don’t understand what’s happening,” Madhav can be heard saying with much disappointment. Something doesn’t seem to sit well.

“I repeatedly told them that, didn’t I? How are we supposed to do it without cones?” Sai Ashwin belts out, before they all laugh sheepishly. Apparently one of them seemed to have forgotten to bring the road safety cones for the run.

A phone call is made and the safety cones are brought. By the time the crew places the cones on the road, the crowd at IC&SR gets bigger. As Sai Ashwin puts on the helmet, prepared to push the throttle, everyone at the venue, including this writer, flips their phone out, ready to capture the moment RFR23 takes off. Until it doesn’t.

There’s some confusion. The audience — mostly students from other colleges who have come for a workshop on Data Science — at the venue, takes a closer look at the RFR23, and has a chat with its crew members. “We don’t have enough voltage to do the run, so we thought it’s better we don’t do it today,” Madhav tells us.

Battery consumption remains a challenge and a vital area of focus, says Madhav. “We always tend to stay between 20% to 80% of the state of charge. There are also smart algorithms implemented in the battery management system to maintain the same voltage and the rate of discharge so that you are still able to hit higher velocities, energy and acceleration,” he says, explaining the challenges in putting together an electric car.

This is certainly not a roadblock but a matter of concern for Team Raftar, as they prep and fine-tune the RFR23 ahead of the upcoming Formula Student Germany (FSG), slated to be held in Hockenheimring, Germany, from August 14-20, 2023.

FSG is an annual international design competition where students from universities across the world build a single-seater, open-wheel race car and compete against participating teams. While the goal broadly is to build the fastest car, the competition evaluates other important aspects such as the construction, performance, and financial and sales. The competition more or less is a platform where knowledge and ideas are exchanged; it gives students an opportunity to network and at the same time, learn from each other.

Reliability first

There are three main categories at FSG: combustion, electric and driverless. Over the years, Raftar has participated in the international competition four times in the combustion category. This will, however, be the first time the team will compete in the EV category.

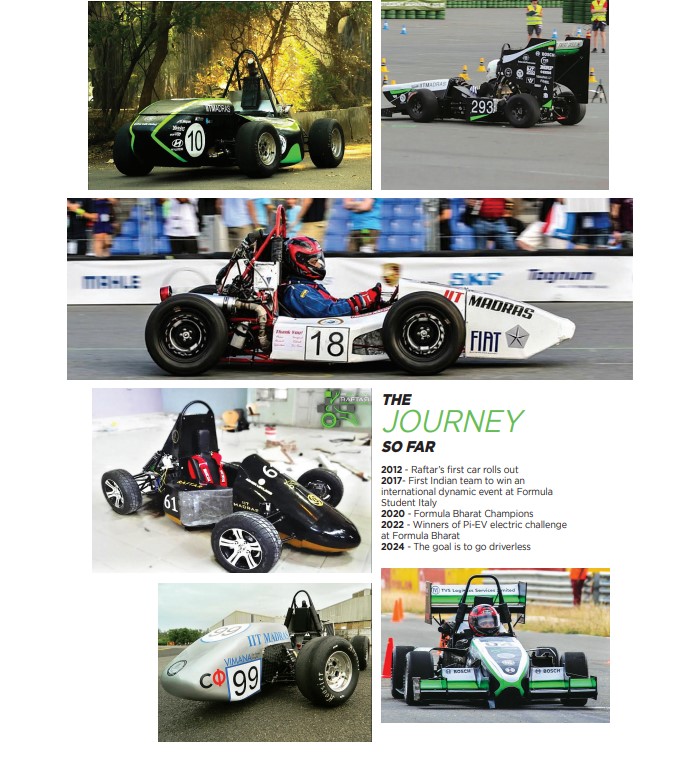

Ever since its inception in 2012, Raftar, which takes up the monumental task of building a fast yet reliable Formula Student race car every year, has mostly been working on combustion engines. The team has won a number of awards and laurels in national and international competitions including being the first Indian to win an international dynamic event in 2017, and a Formula Bharat champion in 2020.

Given the rapid growth in electric vehicles in the country and as well as the world at large, the RFR23 is Raftar’s latest offering. However, that was not the main reason, asserts R Harish, who is the current sponsorship lead and powertrain engineer of Raftar.

“If you look at teams from Germany, which we want to compete against, we have always been given excuses that Germany teams have accessibility to high power combustion engines while it is not available in India,” he says, adding, “We have always been limited in our performance even if we put the best of our abilities. But we are not limited by this in the electric category; we have the best motors available in India and Europe.”

“If you look at teams from Germany, which we want to compete against, we have always been given excuses that Germany teams have accessibility to high power combustion engines while it is not available in India,” he says, adding, “We have always been limited in our performance even if we put the best of our abilities. But we are not limited by this in the electric category; we have the best motors available in India and Europe.”

Therefore, the construction of an electric car will hopefully ensure a level-playing field for both India and Germany, adds Harish. Building an EV, however, was even more challenging than a combustion vehicle since the team has, over the last 10 years, mastered itself in combustion engines.

During the thick of the pandemic, when the nation was under lockdown and when students were at the confines of their homes, Team Raftar decided to draw out a design phase that would last until the students came back to the campus to assemble and build the car. Until then, the design, calibration and prototyping was done in silico.

After several iterations, once the design was finalised, Madhav says that they would go to their faculty advisor, Prof Satyanarayanan Seshadri of Applied Mechanics, for additional inputs and advice. The final design was completed by the end of 2021 and the RFR23 was launched in November 2022.

As soon as Satya was on board, he wanted to reset Raftar’s thinking. “The objective was not to build yet another race car. With the electric platform, it gave us the opportunity to innovate. The way I look at RFR23 is that it’s a technology platform, which will be used for testing various elements of electric propulsion,” says Satya, adding that the team worked with the IIT-M developed SHAKTI processor.

As soon as Satya was on board, he wanted to reset Raftar’s thinking. “The objective was not to build yet another race car. With the electric platform, it gave us the opportunity to innovate. The way I look at RFR23 is that it’s a technology platform, which will be used for testing various elements of electric propulsion,” says Satya, adding that the team worked with the IIT-M developed SHAKTI processor.

“We are hopeful that the car will be number one in various competitions,” said Director V Kamakoti while unveiling the car. Earlier this year, RFR23 secured third in the Overall category at Formula Bharat, the national Formula Student competition held every year. The FSG, however, will be RFR23’s biggest test yet.

Familiar terrain

The FSG is split into two main events: static and dynamic; the former not only includes technical understanding but also economic as well as planning and communication skills. The dynamic category is where the car’s performance is tested for acceleration, endurance, efficiency and skid pad among others. The team with the most points ends up winning the competition.

“There is also a cost and manufacturing event where you show the bills for all the materials you used for making the car. Even if there is a single material that is not on the list but in the car, you will be penalised. The judges will question your manufacturing decisions, like, for instance, why did you make it instead of buying it. The static events are a rigorous process,” says Madhav.

The initial challenge Raftar encountered was with funds. A lot of money had to be pooled in as investment since they were making an electric vehicle. Harish credits the faculty members for their consistent support and encouragement.

“We have an advisory board that includes Prof. Satyanarayanan Seshadri, Prof. Aravind Kumar Chandran who helps us on batteries and battery technology, and Prof. V Kamakoti (Director), who helps us with software and cyber security. Prof. Krishna Vasudevan and Prof. Arun Karuppaswamy helped us in the motor controller part.”

Satya feels that in hindsight, they could have done a better job with the branding of Raftar; calling it a platform right from the beginning might have changed its perception and helped them with partnerships.

“The moment you say you are building a student’s race car, the perspective changes. People want to sponsor a few lakhs like a donation. But when you say you are building an autonomous electric vehicle platform, you are taken seriously. Because what we do here is a significant amount of technology development,” he says, adding that talks are on the way to partner with Daimler Motor Company.

The other challenge that Raftar had to fix was the anxiety around electric vehicles, especially given that there were numerous reports of electric vehicles catching fire. Additionally, there was a detailed rulebook that FSG had that Raftar had to adhere to. “We wanted to build a reliable car first and not focus too much on the performance,” says Harish, “We tried to make sure the battery can sustain acceleration as high as 20g (20 times the weight of the actual battery pack) and is crash safe.”

There were about four to five prototypes that the crew members worked on. Satya, on the other hand, says that the fundamental input he gave that helped the team was the FMEA (failure mode and effect analysis) approach. The algorithm that they have devised is based on deep learning, which tries to get input parameters and estimates the remaining charge rather accurately.

“We have implemented an algorithm that estimates the charge remaining in the car. To perfect this algorithm took a long time,” says Harish, adding that the battery pack is air cooled, while liquid is used to cool the motors.

Madhav took over as the captain from Karthik Karumanchi, who is now an alumnus. During the launch of the car, Karthik said that the team’s focus was to build a safe, sustainable and reliable electric vehicle by looking at current issues faced in the industry.

Madhav, Harish and Sai Ashwin were all juniors when they joined Raftar. They have all grown with the team. As Harish jokes, “Whenever we find spare time, we go to our classes.” Madhav concurs. “The thing about Raftar is, it is a very committed team.”

Every year, Raftar recruits a fresh pair of drivers as well as crew members. The driver selection, which happens either once or twice a year, is another rigorous process where the first obvious criterion is passion. “Whoever is interested in driving, we give them a shot provided they have a driver’s licence,” says Madhav, adding that drivers are put to test via go-kart. “We can’t obviously give an expensive car to someone inexperienced.”

Go-karting is a common team activity that Raftar does once every two or three months. Their preferred spot is Chennai’s ECR Speedway, but they also go to Kart Attack. Madhav and his team sit back and evaluate the drivers based on their performance in three key areas: speed, safety and consistency.

“If the driver is going fast but is crashing every alternate lap in a go-kart, that is still okay. But we can’t afford to crash even once during the actual competition because all of these are carbon fibre and cannot take the hit. If any of its edges rubs the wall, it’s going to crumble,” informs Madhav.

Go-karting isn’t the same as driving a passenger car because ultimately, the driver drives a lightweight vehicle. This naturally yields a big difference in terms of performance. For instance, when you break and turn a go-kart, it runs the danger of losing grip on rear tires. “Go-karts tend to oversteer so it’s very easy to lose control in a corner. It’s understandable in the first lap but by the third or fourth lap, the driver should be able to adapt to it. It also matters how you combat oversteering during the driver’s selection,” he says, adding that drivers get two 10-minute slots during the selection.

Raftar selects six drivers in total. The FSG allows teams to register four to six drivers and can run all the events with three drivers. The current drivers, Madhav and Sai Ashwin, will pass on the baton to their juniors next year and take up the role of mentors.

A race against time

There isn’t much time left for Raftar, even though the RFR23 requires quite a bit of fine-tuning before they wind down the testing phase. Some of the critical parts are still stuck in customs, while there are a few components that have to be procured. At any cost, the cutoff time is the end of June.

Since it’s a fully-electric vehicle, it runs the danger of shipping hazardous goods on-air, which leaves them a 20-day transit time. The RFR23 cannot be flown in its current assembled state; the crew members have to reassemble the car in Germany before the competition, which gives them a two-week window. Which also means that in the beginning of July, Team Raftar will have to start packing the car.

At the same time, there is an air of excitement among students; some of whom will fly to Germany for the first time. This, however, is not Raftar’s first time at FSG. In 2018, they made it big by becoming the only Indian entrant to participate at FSG. They qualified for the third time in 2019 and came third in Cost and 11th in Business Plan in Static events for the combustion vehicle category.

The RFR23 has been designed to produce a maximum torque of 109Nm and can clock a maximum speed of 150kmph. Madhav says that the team takes the car out to a race track in Chennai’s Padi for the actual endurance and reliability testing, while occasionally taking it for a spin on campus.

Though they are aware of the speed restrictions on campus, Madhav remembers the surreal feeling he had when he sat in the driver’s seat once. During one of the tests in the wee hours on campus, Madhav thought perhaps he should try and push the car a bit more. He ended up clocking 35 to 40Nm.

The difference in power was visibly evident. “Like when you press the throttle and you actually get slammed back in the seat, that is when you realise how powerful the car is,” he says.

RFR23 is the first electric car designed and built by Team Raftar. The Formula Student Germany is scheduled to take place from August 14-20. For more details, check out Raftar’s website: https://www.raftarformularacing.com

What started as an intimate group of motorsport enthusiasts, Raftar has grown to become one of the successful Indian teams in the combustion engines category. In fact, when Raftar built its first car – RFR12 – on par with international standards, all they had was ₹10,000 in hand and a few second-hand parts at their disposal. They went to the Silverstone Formula One Circuit in 2012, where the RFR12 received praise from the judges of Formula Student UK when it was declared the least expensive Formula Student car of the competition. Their faculty advisor then was Prof. A Ramesh.